re-entering-the-classroom-in-a-time-of-trauma-and-stress

January 12, 2022

In May 2021, my husband and I took our eight-year-old to the zoo. It was the first time we had taken our youngest on any significant outings in over a year. He was so excited to go and he eagerly made a list of the animals he just had to see. He eagerly pulled us through the zoo, selected a new hat as his souvenir, and made note of the treats he was contemplating for later in the day. With attendance capped at a third of capacity, it was a fairly sparse crowd. But for my son, who had not been around so many people in quite awhile, it became a bit overwhelming. His anxiety became palpable as he saw more people gathered in the single area open for lunch. As he began hovering closer to me, he told us, anxiety clear in his voice, how surprised he was to see so many people. And it made me realize that this transition back to pre-pandemic activities wasn’t going to be a simple or straightforward transition.

I’ve thought a lot about the zoo excursion as higher ed institutions transition back to on-campus learning and how important it is that we think about the ways in which that re-entry might affect us emotionally and psychologically. We’ve spent the greater part of the last year socially distanced, confused, and anxious about the changing viral landscape. Going back to busy campuses may exacerbate these concerns and lead to some conflicting emotions.

In this shift back to on-campus learning, I am reminded of how astronauts describe their experience of reentry. I remember learning about how astronauts describe the dramatic return to Earth and the dizzying side effects they experience physically and mentally. I think this is a good way for us to think about what we have experienced in the last year -- like we’ve been on this long flight into outer space, and we are reentering back to Earth. And now we have to address the challenges of the actual re-entry and how we feel once we are back.

Our reentry happens against a backdrop of increasing concerns about stress and mental health. The most recent Stress in American SurveyTM by the American Psychological Association found how profoundly the pandemic has affected our stress. Almost half of the respondents indicated that they felt uneasy adjusting back to in-person interaction, regardless of their vaccination status. Gen Z adults (aged 18-23), the age of many of higher education students, was the most likely to say their mental health worsened in the pandemic.

We have lived through (and continue to live in) a global pandemic that has taken the lives of over 800,000 people in the US alone. You don’t go through this sort of one-in-a-lifetime experience and expect to not be somehow affected by it. The pandemic created a huge amount of stress and uncertainty that changed the way we lived our lives and affected our sense of safety and security.

A lot of people may think that we’re returning to life as we knew it before the pandemic. But the people we are, that we’ve become, are not the same as before. The lives lost and the psychological sense of safety that we lost all add to our individual and collective trauma and impact our experience of reentry. Not everyone will experience reentry in the same way, but the following strategies may be helpful in addressing the transition for many students, staff, and faculty.

Validate what people are feeling.

During re-entry, people may feel a range of emotions from anxiety, stress, excitement, to joy (and everything in between). Acknowledging this range and the conflicting nature of these emotions can help students feel like they’re in a supportive environment that acknowledges their discomfort. Part of this validation also means acknowledging the loss and trauma students may have experienced in the last year. As an instructor, articulate some of your own feelings, including both your excitement to return and your own anxiety about this transition. Check in regularly with students throughout the term, as emotions are likely to change.

Foster connectedness.

We’ve spent the greater part of the last year in a sort of odd combination of being over-connected via Zoom, yet also feeling disconnected and removed from our networks. A return to full in-person learning activities might feel a little awkward for students and instructors. There will be sophomores who have never been on their college campus before, mingling with freshmen who spent the last year of high school online and will be acclimating to both being a college student and returning to on-campus learning.

All students benefit from activities that foster a sense of connection to others. You probably already have some beginning-of-the-term strategies or activities to foster connection. Consider extending those activities throughout the entire term to help foster a deeper sense of connection. For example, I provide 10 minutes in class each week for students to connect with one another in small groups and talk about how they’re doing. Consider grouping students randomly each week and having them answer an icebreaker-type question so they can get to know as many students as possible throughout the term.

These opportunities can also be extended online through discussion boards or virtual discussion groups. Encourage students to form study groups and give them time and space to do so, either through an online discussion board or in class. To foster more connection between you and students, continue to hold online office hours, so students can more easily connect with you outside of class. And finally, be mindful of how connected you are feeling, and to foster connection with your colleagues as part of your own wellbeing.

Promote reflection and mindfulness.

Faculty, staff, and students can benefit from time to really reflect on how they are feeling and being mindful of what they are experiencing. There may be a “go-go-go” mentality as we transition back. Take time to pause and reflect. Give everyone time to take a step back and assess what’s happening individually and within the larger learning environment. Use online discussion boards, polls, or surveys to promote self-reflection and ask students how they are managing their emotions or coping with stress or how the class is going. Practice and model self-reflection and self-care for your own wellbeing. You can’t be present as a fully effective instructor if you are struggling. So don’t forget to give yourself some time to reflect about how you are feeling in this process and what you need.

Normalize help-seeking.

Normalizing a focus on mental health and help-seeking can help students find support to address stress, anxiety, and trauma. With greater reflection and mindfulness, students (and instructors) may recognize the need for help. As an instructor, it helps to be open with students about the importance of seeking help. Share your own experiences with help-seeking if you feel comfortable doing so. Identify resources and explicitly share them with students. Make these resources available in your syllabus, ensuring that all the information (such as URLs and other contact information) is correct and updated. Beyond just putting them in the syllabus, provide a separate handout or post the resources to your LMS.

The key here is to be explicit about the resources available. Students often aren’t aware you have posted the information, so take time to go over the resources. In the past year, I’ve made a point to gently remind my students (and even colleagues) of the services my institution offered when they shared some of their challenges and struggles. I made sure that I had a basic understanding of what services are offered. For instance, I knew that virtual counseling was being offered and the number of sessions students, staff, and faculty could access free of charge and how they could request an appointment.

We can’t predict what the future will bring in this pandemic world. But I don’t think we can or should expect “business as usual.” Being prepared to address the emotional nature of re-entry is one important step as we work towards supporting the wellbeing of our students, our colleagues, and ourselves.

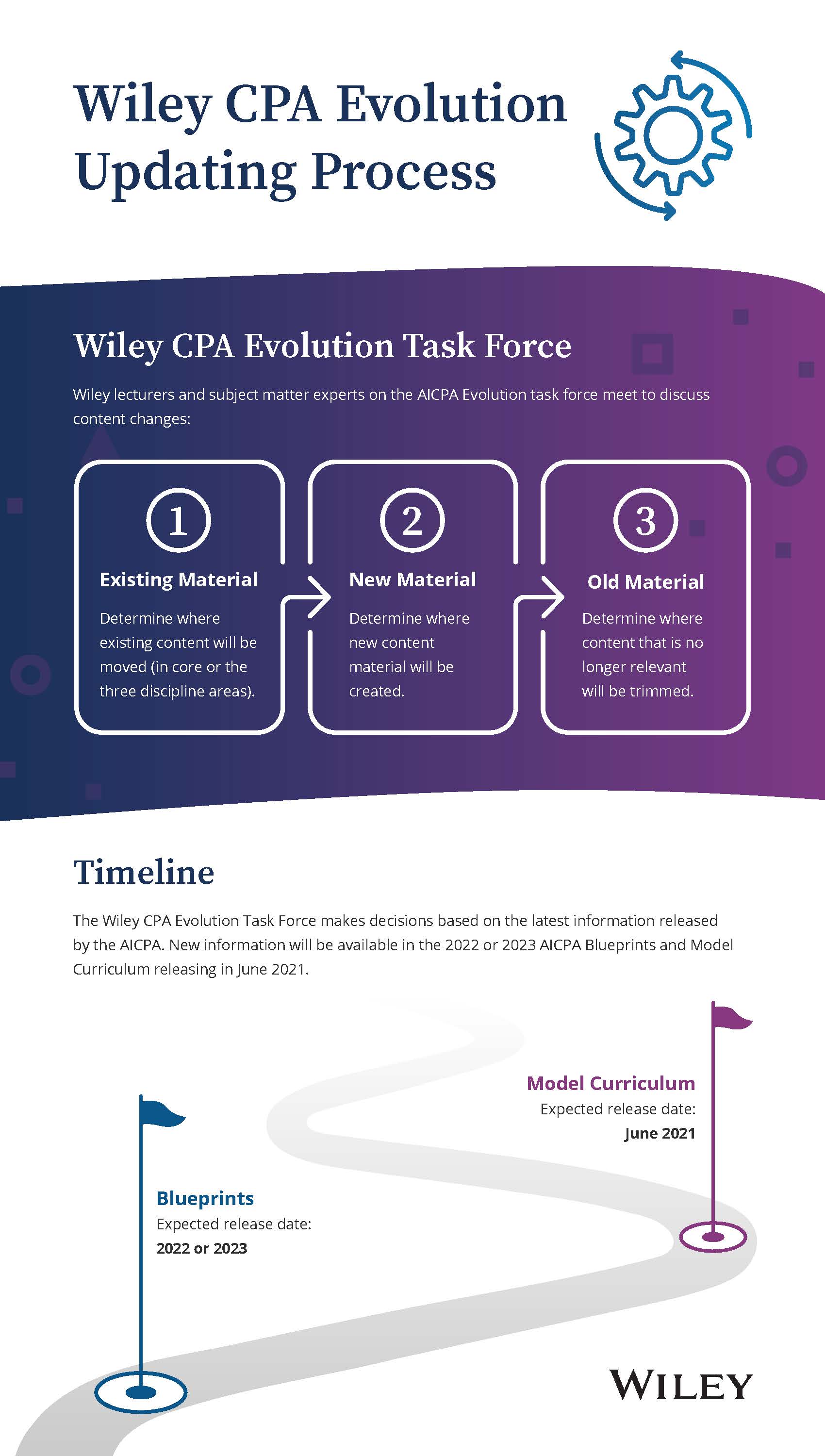

Watch Dr. Hirabayashi's presentation on this topic from Wiley's Wicked Summer Camp.

Author:

Dr. Kim Hirabayashi

- Picture

-

- Description

-

Dr. Kim Hirabayashi is a Professor of Clinical Education in the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California. She has over 20 years of teaching experience on-ground and online and teaches courses in learning, motivation, and human development, as well as supervises doctoral dissertations. Dr. Hirabayashi is currently the Chair of the Organizational Change and Leadership Ed.D. Program. She has a Ph.D. in Educational Psychology, an M.Ed. in Higher Education Administration, and a B.A. English. Her interests include instructional design, academic self-regulation, and student development. Dr. Hirabayashi has previously taught at California State University, Long Beach and has worked in higher education student affairs and community