sustainability-footprint-and-carbon-reduction-in-the-uk-three-perspectives-from-scotland-s-policymakers

March 23, 2020

The recent wave of environmental activism is providing social pressure for governments and policymakers to enact regulation to curb climate emissions. Advocates such as the Extinction Rebellion, Greta Thunberg, and school strikes for climate change have placed the need for operationalizing carbon reduction on the governmental policy agenda. A survey of managing directors in the UK found that legislation is a primary driver for organisations to adopt sustainable development within their business concerns. Simply put, the main drivers for sustainability are government policy (top down) and business pressure (bottom up). Businesses are sandwiched between these change drivers that have influenced the adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and sustainability strategy.

Scotland, host to the 2020 UN Climate Change Conference, has been considered a nurturing ground of capitalist thinking, but it now stands at the crest of a new wave of eco-innovations such as the European Offshore Wind Development Project, tidal energy, and carbon capture and storage (CCS). This recent pursuit of “green” science and industrial endeavour is supported by robust government statutory initiatives such as the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2019.

Sustainability Footprints

Greenhouse gas (GHG) measurement techniques form part of an emerging concept of sustainability footprints, which comprise the use of carbon footprints, water footprints, ecological footprints, and the emerging concept of social footprints to evaluate the present non-financial consequences and future risk implications of strategic decisions.

Contemporary research into sustainability footprint tools has focused on larger organisations, with limited research related to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). However, studies suggest that SMEs are unable to quantify benefits and justify the costs of carbon footprints. Therefore, this article explores perceptions amongst policymakers regarding the use of sustainability footprint methodology by SMEs as tools to assist in carbon reduction.

Making of Sense of the Smoke and Mirrors

To gain insight into the phenomena of sustainability footprints necessitates an examination of GHG emissions data which, in itself, may be useful, but its true value is derived when individuals interpret the data and adopt behaviours or make decisions which are inherently sustainable. Sustainability footprints and their applications as carbon reduction tools are evolving, with its interpretation being influenced by individual perspectives. Due to the ethical dilemma surrounding economic growth and GHG emissions, the individual perspective can be love or hate or ambivalence that is transient. Therefore, in this context, the observation and interpretations of the actions of decision makers are as important as the phenomena being studied.

Perceptions of sustainability footprints are evaluated in this research article through the case studies of three Scottish policymaking institutions: the Scottish government, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), and Business in the Community (BITC) Scotland. Interviews with four policy advisers, comprised mainly of senior management from each organisation, were analysed. Interviewees are policy influencers with practical experience in the collection and analysis of carbon footprint data, thereby able to express relevant views regarding the challenges and critical success factors involved in carbon footprint measurement. This practical element of their experience as policy makers bolsters the validity of this case study, as evident from the following statements.

“As Chief Executive... Well I just facilitate and encourage the internal team [and] allow them the time to focus on it and encourage good results.” — Senior Manager, BITC Scotland

“We do the carbon footprint of the budget internally, so we collect all the information ourselves on emissions and the input–output tables. When we commission it, it is mainly provision of consumption data that is required for the contractor to do their work.” —Senior Manager, Scottish government

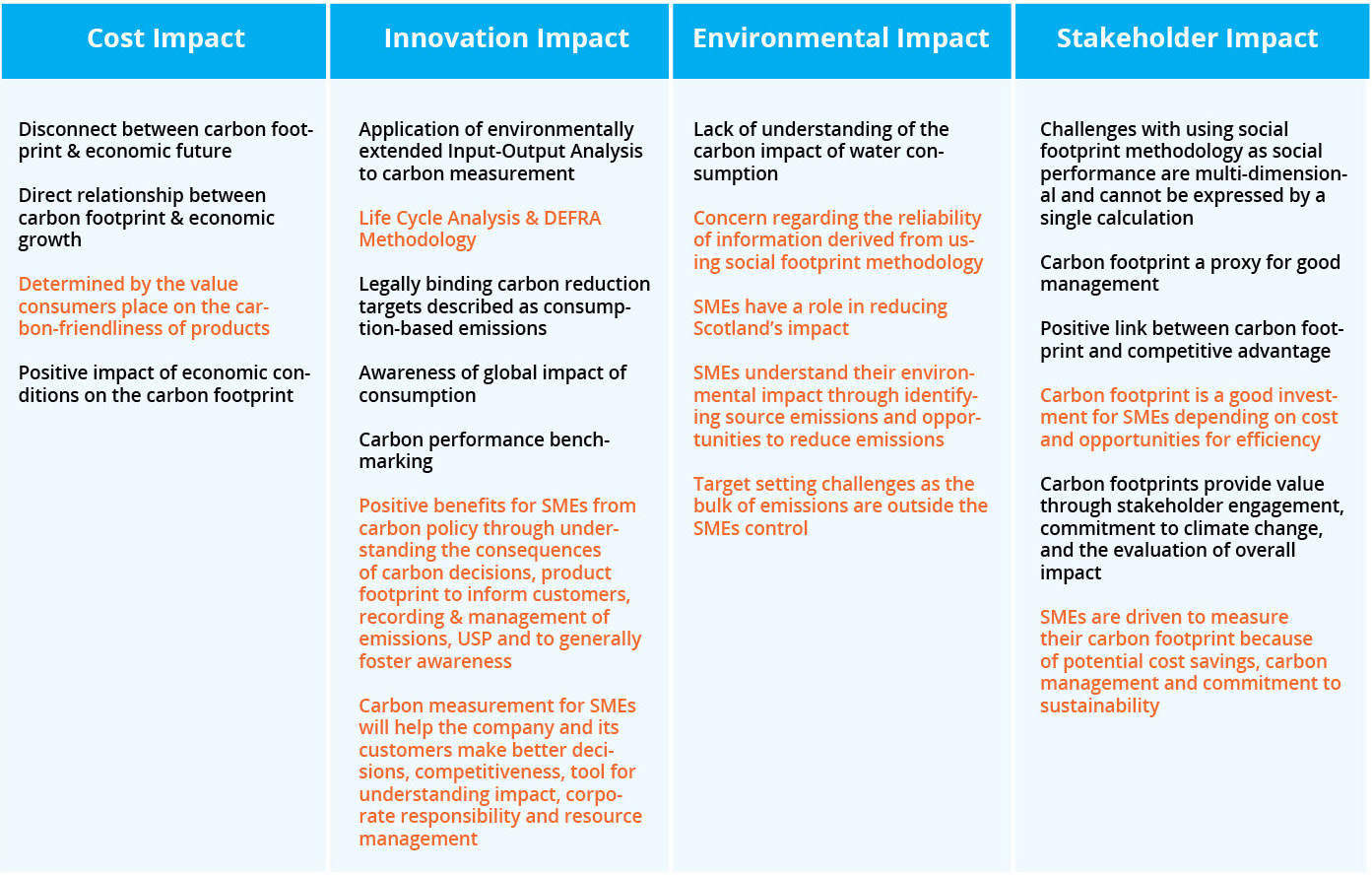

Perceptions of sustainability footprint measurement are presented in four main enquiry themes:

- Cost Impact: Risk and financial capital resource allocation

- Innovation Impact: Product and process innovation

- Environmental Impact: Energy and water usage and emissions and waste

- Stakeholder Impact: Anthro capital resource allocation

The triangulation of secondary data such as CSR reports, environmental audits, and policy and legal instruments are used to corroborate whether sustainability footprints contribute to improved business performance.

Stakeholder Backgrounds

Each policymaking institution provides a unique contribution to the policymaking landscape within the Scottish/UK context. The Scottish government is leading this transition to a low carbon economy by enshrining the requirement for regular reporting of GHG emissions performance by public bodies. The Environmental Economic Analysis unit provides analysis of environmental data such as GHG emissions to allow Scottish ministers to make informed decisions as to the achievement of emissions reduction targets.

SEPA was established by the Environment Act 1995 to regulate and monitor activities relating to Scotland’s environment. Since its inception, the organisation has assumed the mantle for promoting environmental best practices by publishing an annual environmental report every year since 1999. Unsurprisingly, SEPA has actively measured its own carbon emissions since 1997.

BITC Scotland views itself as Scotland’s champion for better business practices. Established in 1982, the mission of this Prince’s Trust organisation is “Building better business for a better Scotland” by creating consensus within the business community for the adoption of sustainable business practices. One of the organisation’s key initiatives is the Mayday Network—a collection of businesses engaged in taking action on climate change. Since 2007, the Mayday Network has encouraged voluntary annual reporting of GHG emissions by its 3,800 member organisations.

Cost Impact

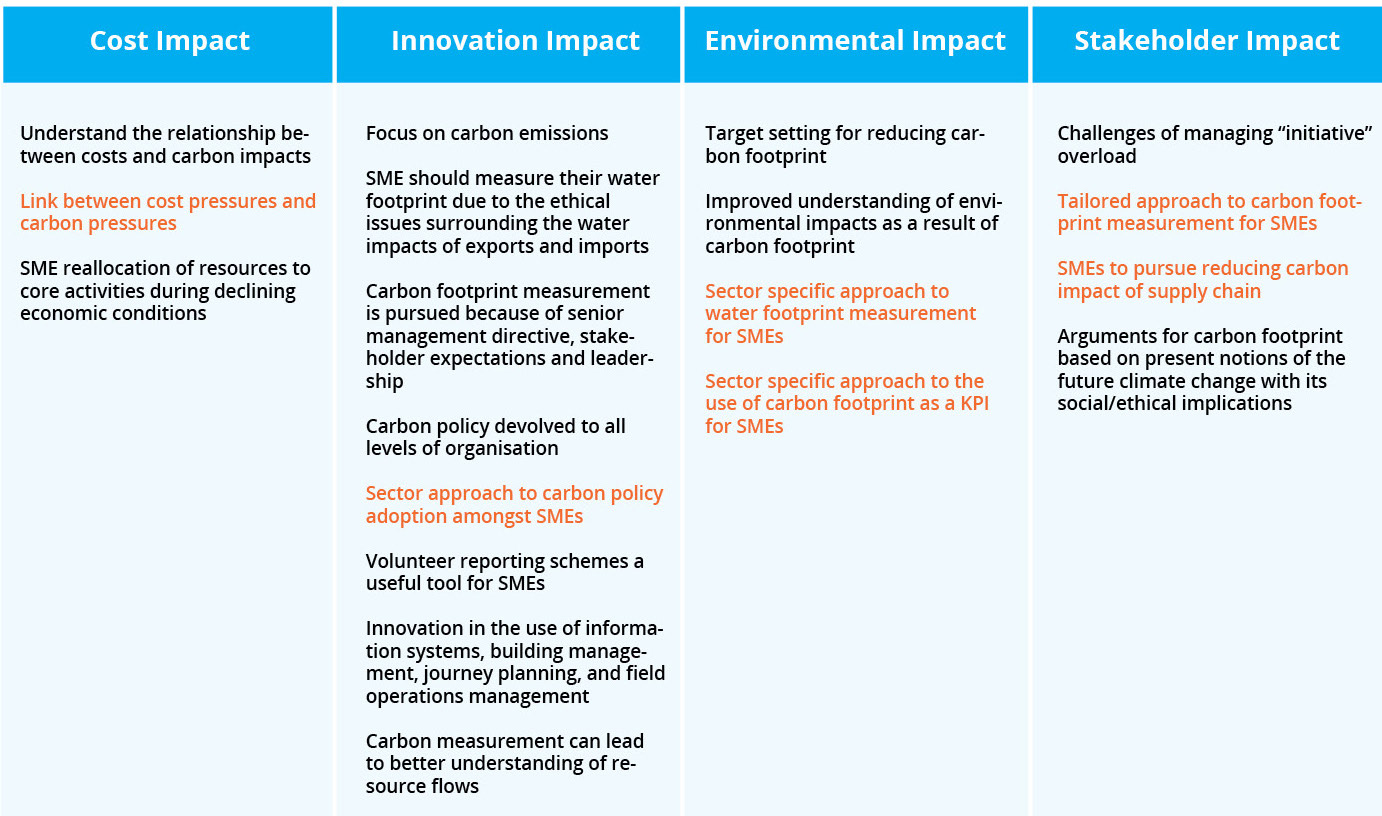

Perceptions of cost impact and its effect on SMEs vary with the functional or strategic orientation of the policymaking unit or institution. Government policymakers frame cost impact within a macroeconomic shroud, stating a disconnect between carbon footprint and Scotland’s economic future. However, they do acknowledge that a direct relationship between carbon footprint measurement and Scotland’s economic growth is mainly due to higher economic growth as it contributes to higher GHG emissions. The extent to which SMEs can benefit from carbon footprint measurement in terms of cost impact is determined by the overall value customers place on the carbon-friendliness of products and services as purchasing criteria (Figure 1).

As Scotland’s environmental champions, SEPA policymakers consider carbon footprint measurement as providing businesses with an understanding of the relationship between cost and carbon impact. The link between carbon pressures and cost pressures is apparent, especially as SMEs are perceived to reallocate resources to core activities during declining economic conditions (Figure 2).

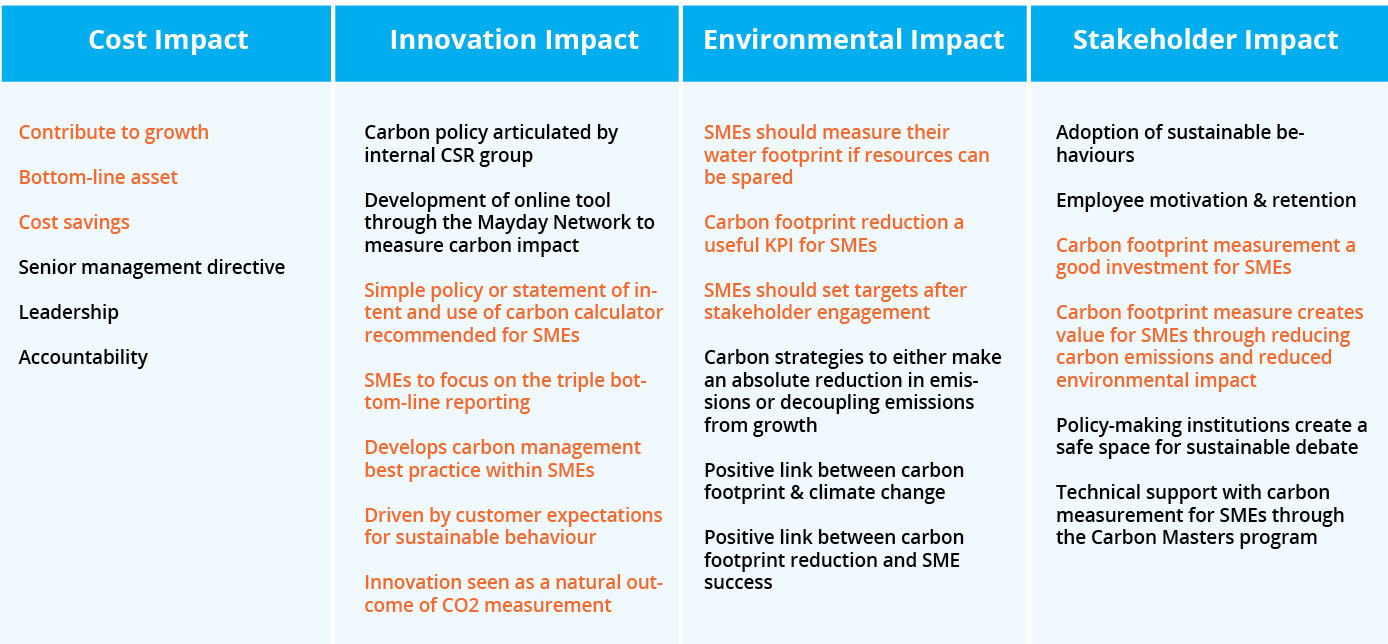

As part of the Prince’s Trust, BITC Scotland is not burdened by cost pressures as a result of carbon footprint measurement within the organisation due to senior management commitment. However, from an operational perspective, they contend that SMEs must consider carbon footprint reporting as a resource and, more specifically, as a bottom-line asset that contributes to growth and provides cost savings (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Scottish government interviewee responses

Innovation Impact

The Scottish government, through its program to measure Scotland’s carbon emissions, adapted extended input–output analysis to carbon footprint measurement. Through the implementation of this innovation, the government gained a better understanding of the global impact in terms of carbon emissions of Scotland’s consumption. This enhanced understanding has contributed to the development of carbon performance benchmarks and of legally binding carbon reduction targets.

The use of Life Cycle Analysis and methodology employed by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) for carbon footprint measurement are perceived as useful tools that will engender innovation within SMEs. Innovation impact of carbon footprint measurement is viewed as yielding positive benefits for SMEs, such as effective carbon policy through understanding the consequences of carbon decisions, measurement of product carbon footprint to inform customers, and the recording and management of emissions and carbon footprint, in itself, creating a unique selling proposition. Government advisers postulate that carbon measurement is a useful management tool for SMEs that builds awareness of environmental impacts, helps customers make better decisions, and promotes competitiveness, corporate responsibility, and resource management (Figure 1).

At SEPA, there has been a strategic focus on carbon emission reduction since 1997. Carbon footprint measurement is pursued due to senior management directives to meet or exceed stakeholder expectations for environmental performance and to provide best practice leadership. The organisation’s carbon policy is devolved to all levels of the organisation and has led to innovation in the use of information systems, building management, journey planning, and field operations management. The policymaking view at SEPA contends that carbon management can lead to better understanding of resource flows. SEPA advocates a sector-specific approach to carbon policy adoption amongst SMEs. Carbon emission reporting by SMEs in voluntary schemes, such as the Mayday Network, is considered to drive innovation and further opportunities to the area of water footprint, uncover the ethical issues surrounding the water impacts of exports/imports, and develop new products, services, or processes to combat these new challenges (Figure 2).

Within BITC Scotland, the carbon footprint measurement is philosophically considered a component of CSR, with carbon management policy being articulated by an internal CSR group. The organisation’s ethos to promote carbon footprint measurement as a tool and the entire CSR agenda contributed to innovation in voluntary carbon reporting through the online Mayday Network scheme, which helps SMEs monitor carbon emissions and environmental impact through an annual reporting cycle.

Policymakers at BITC Scotland perceive SME adoption of sustainability footprint tools, such as the carbon footprint, is driven by customer expectations for sustainable behaviour. They recommend that SMEs produce a simple policy or statement of intent regarding carbon footprint measurement and use a carbon calculator to assist with carbon footprint reporting. The implementation of these measures is perceived to contribute to the development of carbon management best practices within SMEs. Innovation is seen as a natural outcome of carbon footprint measurement, with the ultimate goal for SMEs to utilise triple bottom line reporting (Figure 3).

Figure 2: SEPA interviewee responses

Environmental Impact

Due to the macroeconomic orientation within government policymaking, there is limited understanding of the environmental impact of carbon emissions as a result of water consumption within Scotland. The policymaking focus on carbon emissions reduction has contributed to “carbon myopia,” a concern regarding the reliability of information derived from using social footprint methodology. Critically, SMEs are considered to have a significant, although limited, role in reducing Scotland’s emissions due to target setting challenges, as a great proportion of SME carbon emissions are outside their sphere of control or influence. However, carbon footprint measurement is perceived as helping SMEs understand their environmental impact through identification of source emissions and development of mechanisms to reduce those emissions (Figure 1).

As an environmental regulatory body, SEPA’s use of carbon footprint measurement techniques has contributed to an improved understanding of its environmental impact. This enhanced understanding has resulted in effective target setting for carbon footprint reduction. Policymakers at SEPA, however, advocate a sector-specific approach to the use of carbon footprint and water footprint measurement as KPIs for SMEs (Figure 2).

Policymakers at BITC Scotland are convinced of the link between GHG emissions and climate change and, by extension, the link between carbon footprint reduction and SME success— a conceptual leap which is unique amongst policymakers within the Scottish context. In their view, the objective of carbon strategy is to either make an absolute reduction in emissions or decouple emissions from growth. Policymakers at BITC Scotland recommend carbon footprint reduction as a useful KPI for SMEs, with reduction targets being set after meaningful stakeholder consultation. The promotion of CSR and triple bottom line reporting is a key aim of BITC policymakers, suggesting that water footprint reduction is a useful strategic objective for SMEs if resources can be allocated to the measurement of the organisation’s footprint (Figure 3).

Stakeholder Impact

The adoption of carbon footprint measurement is perceived by government as a proxy for good management, providing value through stakeholder engagement, commitment to climate change, and through having a useful tool for evaluating overall impact and maintaining competitive advantage. Despite this, government policymaking orientation postulates that the challenges with using social footprint methodology to measure social performance are multi-dimensional and cannot be expressed by a single calculation. Carbon footprint is a good investment for SMEs depending on cost and opportunities for efficiency contributing to positive stakeholder impact because of potential cost savings, carbon management, and commitment to sustainability (Figure 1).

SEPA policymaking orientation considers carbon footprint measurements contributing to stakeholder impact, as carbon emission calculations are based on present notions of future climate change and the social and ethical obligations of individuals and businesses to improve resource use. A tailored approach to carbon footprint measurement is preferred for SMEs, one that is aligned to their existing capabilities with a long-term objective to reduce the carbon impact of their supply chain. However, the success of carbon emissions reduction must overcome the challenges of managing “initiative” overload when other organisational initiatives are also mission-critical (Figure 2).

Figure 3: BITC Scotland interviewee responses

As a key policymaking institution, BITC Scotland views its role as creating a safe space for sustainable debate, as well as providing technical support with carbon footprint measurement for SMEs through the Carbon Master’s Program. Policymakers at BITC Scotland contend that carbon footprint measurement contributes to the adoption of sustainable behaviours and better employee motivation and retention. It is also perceived as a good investment for SMEs by creating value through reduced carbon emissions and reduced environmental impact (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The role that SMEs can play in helping Scotland to achieve its carbon reduction targets is not universally accepted by policymakers. This is due to the differing philosophical positions of each policymaking institution. Legislatively, the policymaking climate has been dictated by the weathervane of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act, but mechanisms by which SMEs can comply with the spirit of the law are yet to be conceived.

Policymakers are fully aware that during challenging economic conditions SME resource allocation may be focused on “bottom line” results, to the detriment of “triple bottom line” outcomes. Intervention amongst senior advisors is deferred to allow market forces and customer valuation of low carbon products and services to determine the cost–benefit to SMEs. Different methodological approaches to carbon footprint measurement advocated by policymakers abound. These extremes are underscored by a “carbon myopic” view of environmental impact, one that is focused on GHG emission reduction and has a limited emphasis on water or social footprint measurement.

Despite the lack of consensus regarding a framework to stimulate SME adoption of sustainability footprint tools, policymakers perceive these tools to be a valuable investment of SME resources to identify areas of environmental impact as well as cost. Scottish policymakers have a unique opportunity to combine groundbreaking environmental legislation with clear policy mechanisms to improve SME adoption.