4-big-reasons-students-cheat

September 28, 2020

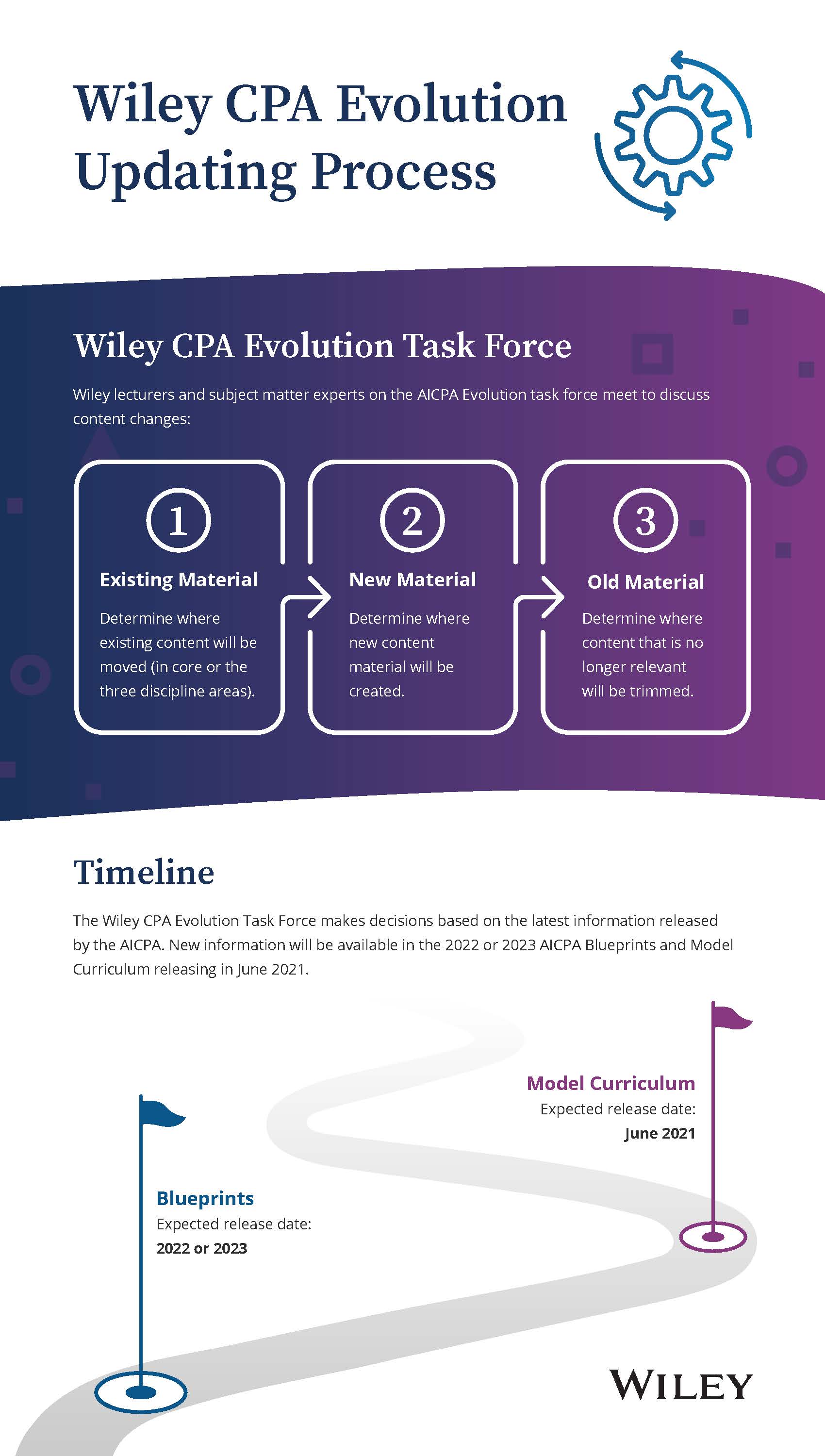

The Science Behind Why Students Cheat

Our country’s response to COVID-19, which led to a sharp, unexpected rise in unemployment, has added to the pressure today’s college students already feel to succeed. But as courses remain online and stress mounts, the question remains: Will students be more likely to cheat to get ahead?

The answer is a resounding “well, maybe.” Wiley conducted a survey regarding academic integrity with 789 instructors responding, and 93 percent believe students are more likely to cheat in an online learning environment. And 72 percent of those teachers who now use technology to deliver their exams and assessments are afraid that cheating may be more prevalent than ever before.

However, other studies indicate higher levels of academic dishonesty in live courses vs. online ones, and it remains to be seen whether the increased volume of online courses will shift the ratio. What we do know is that there will always be those students who cheat, and the reasons they do so are rooted in science.

David Rettinger, Ph.D., professor of psychological science and director of academic programs at the University of Mary Washington, is an academic integrity expert who claims that students who are prone to cheat in class will do so in other areas of their lives. “Cheating in school is associated with real-life future behavior like cheating in relationships, cheating at work, taking credit for other people’s ideas, lying to customers, inflating insurance claims, tax fraud—you name it,” he says. When you help students value integrity in your course, you help them understand their role as honest members of society.

So, why do students cheat? The surface reason is that they believe they can get away with it—but the psychological motivation goes much deeper. According to Rettinger, there are several factors based on psychology, sociology, and the science of learning that contribute to academic dishonesty.

1. Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief that you can doing something. Students who lack self-efficacy aren’t confident that they can complete an assignment or do well on a test. And when they think they’re incapable of doing the work, students are more likely to cheat. Even high-achieving students can exhibit low self-efficacy—especially if they’re under a ton of external pressure to achieve greatness, whether that’s passing the CPA exam or getting into medical school. In these pressure-cooker situations, getting anything lower than an A simply isn’t “good enough,” and if they don’t believe they can make the grade in a challenging course—especially one they need to graduate—they too will resort to cheating.

2. Learning Motivation

There’s intrinsic learning, which is self-driven, and extrinsic learning that’s dependent on external factors. Students who fall into the intrinsic learning camp love to learn for the sake of learning, and therefore cheating is much less prevalent. However, extrinsic learners use learning as a means to an end, whether that’s getting into medical school, landing a job after graduation, or simply getting good grades to please their parents. “You can help students care less about grades and their external pressures by reminding them that they’re in college to acquire information and skills that will help them later in life—not just to check a box off,” Rettinger says. This mind shift turns the end goal from one of “academic achievement” to “competency,” a life skill that will serve them well in class and in their future careers.

3. Social Situational Factors

We tend to share the attitudes and beliefs of the people we associate with. Taking it one step further, we also behave in the same way as our closest friends do. “The actual belief that their peers are cheating is one of the most important predictors of academic dishonesty,” Rettinger explains. “Being surrounded by cheaters has an almost contagious effect.” Likewise, students are less likely to cheat if their group engages in authentic, honest learning. And the best way to thwart cheating is to make it seem socially undesirable—something that only an outsider would engage in. This helps connect the behavior of cheating with being “unliked” or even “unsuccessful,” which will deter students from doing it themselves.

4. Institutional Integrity

One of the best ways to drive down cheating is to let students know that your institution embodies a culture of academic integrity. In other words, they attend a school that doesn’t tolerate cheating and there’s a practice in place that can identify cheaters and punish them accordingly. This helps negate “neutralizing attitudes,” which is when students trick themselves into thinking cheating is acceptable based on their circumstances. An example of a neutralizing attitude is: “I pay a lot to go to this school. Therefore, I deserve to get good grades and I’ll do whatever it takes.” However, students are less likely to act according to neutralizing attitudes when they perceive that their professors and entire institution take cheating seriously.

Instructors can encourage academic honesty by replacing high-stakes exams with low-stakes test-taking opportunities. You can give students a ten-question, multiple-choice test that takes no longer than ten minutes to complete or an open-book/open-note test to relieve some of the pressure to do well. You can also ask students to write the questions to their own exams because when they have more agency over the learning process, they’ll feel more in control and less inclined to cheat.

You can also remind students of their core value system, which likely encompasses traits like honesty and conscientiousness. This will help them recognize when any behavior (e.g., stealing a test, cheating off of friends) goes against their beliefs, and they’ll likely course correct in order to protect how they see themselves and how they want others to perceive them.

To learn more, watch David Rettinger’s on-demand webinar, When Good Students Make Bad Decisions: The Psychology of Why Students Cheat.

Dr. David Rettinger

- Picture

-

- Description

-

Dr. David Rettinger, Ph.D. is Professor of Psychological Science and Director of Academic Programs at the University of Mary Washington. He also is Procedural Advisor to UMW’s student-run honor system. His academic research interest is in academic integrity behavior, having published research on the psychology of cheating in Theory into Practice, Research in Higher Education, Ethics and Behavior, and Psychological Perspectives on Academic Cheating. Rettinger is President Emeritus of the International Center for Academic Integrity, an organization founded to combat cheating, plagiarism, and academic dishonesty in higher education. In addition, he leads the organization's efforts in assessment and survey research, continuing the McCabe academic integrity survey. He earned a Ph.D. (1998) and an M.A. (1994) in psychology from the University of Colorado, Boulder, after receiving a B.A. (1991) with high honors and distinction in psychology from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.