q-a-with-rgs-fellowship-winner-dr-catherine-oliver-animals-of-the-royal-geographical-society

May 20, 2022

In 2020, Dr. Catherine Oliver was awarded a Wiley Research Fellowship in collaboration with the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), which provided her with access to their digitized archives via the Wiley Digital Archive platform.

Dr. Oliver researched the different forms that human-animal relationships take for her project titled Animals of the RGS, which explores the fascinating history of animals as sources of knowledge, companions, and collaborators in the history of geography and exploration.

We recently spoke to Dr. Oliver to find out more about her research.

How did you first become interested in researching animals and their relationship with human geography?

I have been fascinated by animals for as long as I can remember. During my undergraduate degree in human geography, I became a vegan, and this ultimately set me on a path to studying vegan geographies for my Ph.D., before expanding out from activism to research animals themselves.

Animals have a long and important place in geographical study, whether as markers of landscape or as workers and companions in geographical exploration. However, they have often been grouped with a broader idea of “nature,” although more recently in geography, animal agency and place-making has been given more attention.

The opportunity to work with animals and learn about space through non-human perspectives can teach us a lot about the world and help to value environments and species more, inspiring an understanding of the world as more than simply human life.

How does the project you produced as part of the Wiley Digital Archives research fellowship, ‘Animals of the RGS’, fit in with your wider research interests?

The Animals of the RGS project builds upon some of my wider research interests in animal histories and geographies, as well as my ongoing interest in the different forms that human-animal relationships take. It is widely acknowledged that these human relationships with animals are culturally, socially, and geographically influenced, and this work sits within my wider research interest in exploring the role of animals in shaping global history as well as contemporary life.

I am interested in the kinds of spaces that humans and animals are co-creating to learn to live well together. My research on the animals in the Society’s archives applies this lens to the histories of geography. In sharing the stories of animals as companions to and challengers of geographical knowledge, this project is complementary to the wider ethical, political, and geographical aims of my research portfolio.

It’s clear from your work that you have a love for animals. Has studying animals in your research impacted your relationship with the animals in your life or the animals you encounter in nature?

Studying animals has totally transformed the way I think about, value, and interact with animals in the wild or domestic animals. Similarly, being vegan and having a particular ethical stance on our relationships with animals inevitably influences my work. Researching animals has made me understand just how deeply connected we are, and how our futures are entwined. Understanding animals isn’t simply a case of biology or sociology, but about a holistic attempt to find out how they experience the world, and how we can create spaces that enhance both human and non-human life.

Specifically, my research in the Royal Geographical Society’s archives made me respect – as well as mourn – for animals who had been enlisted in geographical expeditions and advocate for recognising their position in the history of geography.

In your research you said that you were surprised to find photograph collections of animals from female explorers as well as men. What else were you surprised to find in the archives?

One of the most surprising things I found – or more accurately didn’t find – in the archives was the presence of “ordinary” animals. In my current main research project, I am researching chickens in London and their global networks since 1850. In the Society’s archives, there were several examples of chickens at markets, as food, and at markets. However, given the ubiquity of free-roaming chickens in almost every society across the world, it was surprising that there weren’t more chickens in the background of photographs in the archives.

Chickens are difficult to herd and to ask not to come into photographic shots. They are also flighty, and likely would not take kindly to being picked out of portraits. In some of the photographs I have been through, I have been surprised by the absence of chickens more so than I have by their presence when I would have expected them to often be part of the landscape.

However, the historical gaze does not attend necessarily to the ordinary or the taken for granted other-than-human world. Reports of chickens the world over were unlikely to be praised or even taken seriously from expedition reports because the public and Society “back home” in Europe were interested in the new, the exotic, and the unusual.

The archive is, of course, limited by the interests and attentions of those who created it and, aside from these few documents, I guess a relatively mundane bird was never going to feature heavily in the archives!

Your research features many different types of materials, ranging from photographs and sketches to manuscripts and pamphlets. Which type of materials did you find most useful for your research?

My process for working in this archive was to begin with photographs. I envisioned the research as having a potentially powerful opportunity to capture the public’s imagination about animals in geography. The first few weeks of my project, I set about collecting and reviewing photographs from the whole archive and of as many species as possible. Some of these I chose just because they were interesting or charming or told us something about how animals were included in geographical exploration.

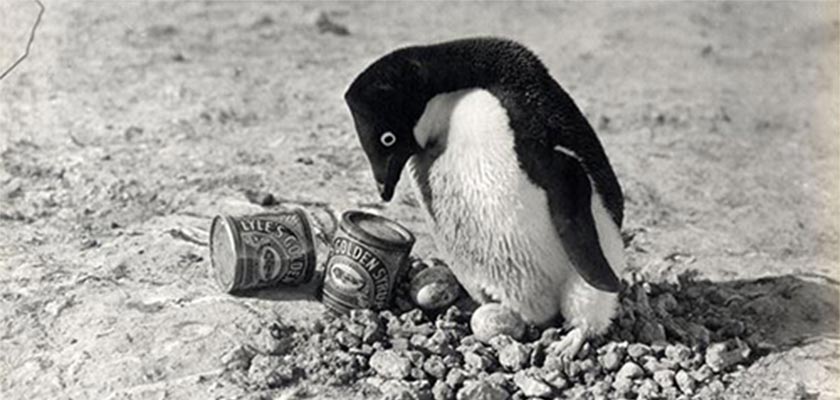

I then worked outwards from these photos to identify who these animals were, which humans they worked with, and what their role or life had been like. This led me into classic geographical stories from new perspectives, like Captain Scott’s doomed Terra Nova expedition via dogs or Shackleton’s photography via Adelie penguins, as well as revealing unfamiliar stories, like the trading of animals at marketplaces across the world.

One of the materials I enjoyed learning about in your research project was the rock drawing from Sudan. Rock drawings often depict very early images of humans and animals, what can we learn from them?

In the history of geographical exploration, animals have not just been companions or workers, but have also been essential to understanding other culture – both contemporary and historical. Artistic and cultural representations of animals are one way that archaeologists and historians can use to interpret past cultures. Often, the aim of studying rock pictures is to understand their artists, their origins, the stories they are representing, and their relationships with the wider world.

The rock pictures I looked at in the archive were photographed by Bill Kennedy-Shaw in 1935 at Jebel Tageru in Sudan. Jebel Tageru is a mountain plateau situated on the southern edge of the Libyan desert, and Kennedy-Shaw had travelled the desert extensively in the 1920s and 1930s as a botanist and archaeologist. The pictures were of cattle, which dominated the earliest rock art in this area, suggesting that these engravings were probably made by cattle herders.

This observation can also tell us about the climate of the region and how that impacted which animals were employed: based on this evidence, it can be assumed that camels no longer frequented the region as conditions became more arid during the 2nd millennium BC (p.286). Animal art can tell us not just about historical communities and life but also about changing environments.

Which tools on the Wiley Digital Archive platform did you find the most helpful?

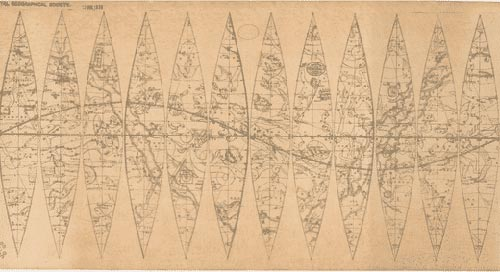

There were two tools that I found particularly helpful on the WDA platform. The first was the visualisation and mapping of the archives built into the platform, meaning you can refine search terms by year, area, and collection. My project took a relatively broad approach to the archives, rather than a specific time or place so the way I used this tool was to ensure a good spread of evidence across time and the globe.

For example, these visualisation tools also allowed me to identify the “first” instances of animal species in the archives, and their presence over time. This led to interesting discoveries such as the growth in the presence of dogs in the geographical archive in the 19th Century, coinciding with wider use of cameras. As evidenced in the huge number of photographic portraits of expedition dogs, this suggests that new technologies allowed the role of animals to be better documented in the archive. For dogs, cameras provided an outlet to frame them as collaborators and companions, as well as workers.

The second helpful feature of the WDA platform for my research was the introduction of automatic text reading, meaning that manuscripts were translated into text that could be searched and copied easily. This update was fantastic for my research, allowing me to quickly scan bulks of text that otherwise I would not have been able to get through. It also meant new materials could be pulled up through the search terms that hadn’t necessarily been “tagged” with a full list of keywords. This allowed me to engage much more easily with manuscripts and diaries.

Which document were you most excited to find on the Wiley Digital Archives platform?

My favourite image in the archives was one that I didn’t know exist, but which can tell us a lot about human love for animals and how geographical exploration was a public event.

The image is of an Adélie penguin – a small species of penguin common along the entire coast of the Antarctic continent – photographed in 1911 by Herbert Ponting on the Terra Nova expedition as part of an “attitude survey.” These species of penguin have been described as the most “man-like of the penguins” and this anthropocentric charm attracts humans to them.