exploration-of-a-forgotten-archipelago-a-qa-with-dr-alicia-colson

March 02, 2022

In 2020, Archaeologist & Ethnohistorian Dr Alicia Colson was awarded a Wiley Research Fellowship in collaboration with the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) which provided her with access to their digitized archives via the Wiley Digital Archives platform.

Dr. Colson researched the island of Santa Catarina, Brazil for her project titled From ‘Banishment’ to ‘Cool’: a chairborne exploration of a ‘forgotten archipelago’, which explores the fascinating history of Santa Catarina’s archipelago through archival maps and primary sources. Dr. Colson's research is visually displayed in a creative story map which visually displays her findings, which you can read for yourself here.

We recently spoke to Dr. Colson to find out more about her research.

Q1. How did you first become interested in researching the ‘forgotten archipelago’ Santa Catarina, Brazil?

I spent part of my childhood living on the main island of Santa Catarina. During my time there, I visited many of the places on that island as well as mainland Brazil, across the Canal so I had a good idea of what I should be looking for and where. I’ve been fascinated by maps and the types of information that could be recorded by them and what they can tell us about a place ever since I encountered a world map when I was in primary school in Brazil and started to study geography. We had to find which countries our families were from by consulting on a large map of the world and show our classmates. It was at that point I discovered that the UK was so tiny in comparison to Brazil. This was a shock as people implied in their speech that the UK and US were so large, which probably related to its importance in their minds. The way that it was spoken about implied, to me, aged 7, that the UK was large. I became more interested in the island as I realized that many environments existed in one island. In the morning I’d swim in a freshwater lagoon, in the afternoon I might climb a mountain and experience variegated forest cover (Mata Atlântica, coastal plain lowland forest, montane forests, ‘campo rupestre’) reached by walking up dirt tracks, all the while picking wild fruits and knowing monkeys were watching.

Q2. How does the storymap you produced as part of the WDA Research Fellowship fit with your wider research interests?

I’m fascinated by images. They contain vast quantities of information which are often tough to unpick. But I know the real question is what is the context within which an image should be understood, how to unpick it. The phrase ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ is true. In looking at Santa Catarina I was likely to deal with images created by a wide variety of people, photographs, paintings, drawings, prints etc. ESRI StoryMap is heavily dependent on visual, rather than textual content so I knew maps and images were the most useful way to start. From having reviewed various ESRI StoryMaps by other researchers I found that the most gripping were those which were both detailed and visually catching. I initially searched for images, i.e. photographs, drawings or prints, and maps. I also looked for letters and anything classified as pamphlets and manuscripts. I was open-minded about what I might find. I knew from my initial examination of the Wiley Database that information existed on the grasslands of southern Brazil, the area we call Rio Grande do Sul, as well as the Centre West São Paulo, upland Rio de Janeiro beyond the coastal ranges and the vast Amazon Basin. I searched for maps, letters, manuscripts, or photos of the archipelago of Santa Catarina from the coast of Brazil. I searched for materials which contained the words ‘Desterro’ and ‘Nossa Senhora de Desterro’ as these are the previous names of the administrative capital for centuries before it was changed to ‘Florianopolis’ in 1894.

Q3. Your research explores the fascinating history of Santa Catarina, which begins with indigenous people and takes us through its history of pirates, European settlers and fortresses right up to modern day. What part of Santa Catarina’s history are you personally most interested in?

I’m interested in several periods. I’m fascinated by the period when the first Europeans arrived in the area and their encounters with the indigenous peoples (the Xokleng or Aweikoma (sometimes called Botocudos)) over the subsequent centuries as immigrants continued to arrive in Santa Catarina from Portuguese lands and elsewhere. I’m particularly curious to know more about the Azorean immigrants and also learn what the travelers from elsewhere in the world thought of the archipelago.

Q4. In your research, you wrote that the maps of Santa Catarina from the 17th century are “political statements”. Why are maps such important sources of information for your research?

Maps tell one how different groups of people organize their physical and mental space. These maps reflect the clash between two European Empires: the Portuguese and the Spanish both attempted to control the archipelago. That control of the archipelago meant that either Lisbon or Madrid could retain their access to Chinese manufacturers of luxury goods using the silver produced in Potosi (current Bolivia) and shipped from either Buenos Aires (Spanish) or Colonia (Portuguese) back to Cadiz or Lisbon. Both struggled to control the archipelago, as well as lands to on the West (the Planalto) and the vast grasslands (Pampas) to the south.

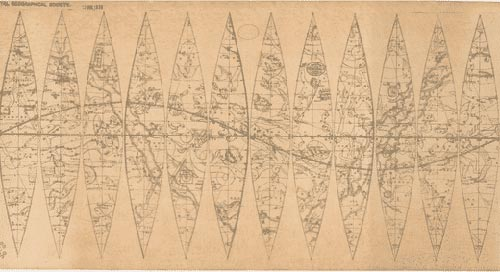

Q5. Your research project explores how maps of the same area change over time and how they are influenced by the powers of the day. What changes do you look for when comparing maps of the same area from different time periods?

I’ll identify the language used and examine the map to establish the outline of the islands and mainland coast in question, to see whether any bodies of water are depicted on the lands in question, or detect a reference to the height of mountains depths of bodies of water. I always look to see if there is a scale and a key to the map, I’ll identify the language(s) used, whether a cartographer or anyone else’s name is on the map. Then I’ll go and find out about their identity and indications of the purposes behind its creation.

Q6. What was your first impression of Wiley Digital Archives? How does it compare to searching in a physical archive?

My first impression that was I was being presented with a feast of unlimited information as the many search tools enabled me to really ‘squeeze’ each resource for information. It’s a goldmine of useful information. It was tough. Just confining myself to working on finding materials for my own project as I could go and search for many useful nuggets of information for different projects that I have already undertaken, or I’ve contemplated.

The biggest difference between searching using Wiley Digital Archives rather than a physical archive is that you’re able to search different types of formats, of data at the same time by using keywords, and that you’re not only obtaining the bibliographic information but the contents of each item. The decisive bonus was that you could read a document, i.e. a manuscript as the search tool had searched handwriting which was otherwise harder to transcribe. I’d expected that I’d have to read the 18th and 19th-century copperplate but here was a tool that transcribed the copperplate text for the reader. Enables me to get to the heart of the matter – quickly.

Q7. What tools on the Wiley Digital Archive platform did you find the most helpful?

Again a tough one as there are several useful tools. I often used the search mechanism which Wiley offered to search for specific pages, or documents to find particular information. It was very useful to be able to search for words within a document as one could identify whether it might be useful or not. Since I knew the dates when place names were changed it proved invaluable to run a search on a word in a range of years. The ability to search within specific time frames enabled me to find a great deal more information than I had anticipated.

I used complex searches (boolean searches) to find a range of materials. Once I’d found an item, let’s say a map, I’d use the WDA tool which enabled me to search within a document. I found these search tools within pre-20th documents incredibly useful especially when dealing with script or long documents. This was particularly useful for searching for whether the word ‘Brazil’ for example was found in the list of countries covered in the first few pages of Mercator’s 1639 Atlas.

Q8. Which document were you most excited to find on the Wiley Digital Archives platform?

I was delighted to see this map entitled “Carta Geo-Hydrographica d’Ilha e Canal de Santa Catharina” by H. L. Niemeyer Bellagarde (1830), only eight years after Brazil’s Independence. The level of detail is such it provides a foil for evidence from multiple sources to tell us something of the history of the archipelago. The depiction of the winds, all of the islands, the churches, the communities both on the islands and the mainland, the anchorages, its 62 sand beaches, surf, variegated forest cover (Mata Atlântica, coastal plain lowland forest, montane forests, ‘campo rupestre’), and fresh water fed lagoons, streams and mountains, as well the little farms as their cultivation reflects changing technologies and so much more.

Q9. Your visual storymap is a creative and effective tool to support storytelling in your research. Do you have any advice for other researchers wanting to visually display their research?

Yes, I have several pieces of advice. Think carefully about the question ‘What is your message for your audience?” “Who are your audience(s)?”. Always use clear and simple language. Jargon and technical disciplinary terminology will just lose you, and your reader. Be prepared to plan, edit, and rewrite your story map. Write a detailed plan of your Storymap project before you load it up on the system. I’d suggest that a draft version at that stage will enable you to test that your idea actually works out. Remember to choose your images with care so that they suit your message and that all copyright hurdles are cleared with the copyright holders before the storymap is released.

Q10. Why do you think digital historical archives are relevant for modern research?

Research has always required access to archives which hold primary sources. Until they were digitized access to maps such as those I consulted were only accessible by very few people who had the means, meant mounting and executing a research project/an expedition: with all the time and resources that entails. So, the existence of digital historical archives is a first and valuable step. Their data does not yield great fruit until tools are created by the appropriate specialists which can enable a wide range of researchers, from many different backgrounds to ‘mine’ and contextualise ‘their’ content (data). Digital content can be used at scale through the use of the appropriate database software. Digital data enables researchers, for example anthropologists, archaeologists, demographers, geographers, historians, or sociologists to ask questions of data which could hardly be formulated, let alone addressed. With the appropriate software tools they have the ability to ‘crunch’ that data at their fingertips. To ‘model’ and to ‘re-think’ Prior to digitization many questions would remain in the air, unformulated and therefore absent from the constant revision that is the delight of the scholar. Opening new worlds – the work on Wiley Storymap raised more questions than it answered.

To find out more about Wiley Digital Archives please visit wileydigitalarchives.com

Connect with Dr Alicia Colson on twitter @colson_alicia or visit her website aliciacolson.wixsite.com

Dr. Alicia Colson, The Explores Club ‘Explorers 50’ Finalist

An archaeologist and ethnohistorian working with computing scientists Dr. Alicia Colson collaborates with indigenous peoples, NGOs, and governments in Canada, UK, US, and Antigua to understand our pasts. Expeditions in Namibia and Iceland encouraged her to practice citizen science. As a Wiley Digital Archive Fellow, her passion to explain to the widest audiences led her to produce an ESRI StoryMap of the Ilhas de Santa Catarina, Brazil, her childhood home. Co-founder of Exploration Revealed, the Scientific Exploration Society's digital hybrid publication with Briony Turner showcases advances in knowledge and peer-to-peer support for those engaged with scientific exploration and adventure-led expedition.