research-supercharged-by-ai

No research exists in a silo. Citation, reference, and peer review are the connective tissue that binds research into a chain of discoveries and understanding. You can trace research, like a family tree of science, back through generations to the ‘primordial paper’ from which all modern understanding sprang.

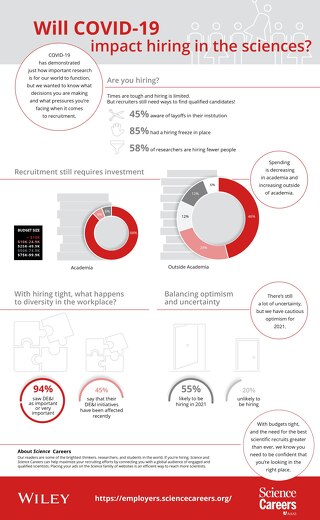

Solving the world’s problems requires research from several fields to align, collaborate, and make unexpected connections. A topical example of this is One Health, the concept that medical, veterinary, epidemiological, and environmental disciplines are intrinsically linked. When developing strategies to tackle a disease like COVID-19 that is thought to have started in animals and then made the jump to humans, these connections are vital.

Technology will be at the heart of helping researchers to make these connections.

Technology already forms the backbone of the traditional connectors through identifiers, standards, and good old hypertext. But the next frontier will use technology to gain insights that would have otherwise been missed and level the playing field across disciplines by improving the discoverability and accessibility of research from around the world.

Artificial intelligence – the use of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence and discernment – is here today, in one form or another. It will only get more powerful as we embed it throughout the research cycle from finding potential areas of study, to translating papers on the fly with incredible precision and domain awareness into languages that open research up to the developing world.

Why stop there?

Leaving aside Newtonian leaps of understanding, research is about asking interesting and important questions and designing a study to answer it. Today, the industrialization of research via paper mills is clearly a bad thing, but in the future industrialization of genuine and high-quality research through artificial intelligence will be within our grasp. If the hypothesis and method are created in a machine-readable and comprehensive way (although the ability of computers to understand natural language will continue to improve) then all that we’ll need to generate findings and a conclusion is to plug in the results. Human researchers will still ask the right question, design the right experiment and generate the results, but they will be assisted by AI that can guide them through that, even generating hypotheses – a use for this might be identifying candidate diseases that might be treated by existing drugs - and then turn results into findings.

More high-quality research equals more high-quality connections and connection opportunities.

The steppingstones to that point will be machine-learning driven aids for human researchers so they can spend more time on asking the right questions and designing the most efficient path to the solution. Leave other mundane, but important, tasks to the machines. AI will point the future researcher to relevant papers, taking them way beyond their traditional corpus of reference. Physicians will find answers in veterinary journals. Vets will gain insight from Earth science societies. AI will guide researchers as they morph into authors – avoiding bias, maintaining ethics, and summarising complex concepts in abstracts created by machine for fellow researchers and for the layperson. Why should those tasks only be gates in a peer review or editorial process, when they can be pushed upstream to the actual content creation process and made accessible for all?

In a world where the status of science and scholarship feels under threat from populism, it will be vital that trust is rebuilt, and research will need speak in a voice that a broad audience can understand. Clear and appealing communication will be vital to those at all levels of education and AI will drive that: a write once – communicate at many levels – system.

Broader readership means more connections.

The ethical conundrum is how, or indeed whether, to enshrine the role of the human researcher as AI becomes more powerful and its capabilities take over more and more of the research process. There are well documented stories of AI bias – it is only as good as the data used to train it – and so care will need to be taken, not only to avoid such problems, but to recognise that we are a long way short of replacing human intuition, gut instinct, and the positive effects of crowd-sourcing insight. Einstein famously made a breakthrough in his theory of special relativity while walking and chatting to a friend and fellow physicist. Will machines ever be able to fire off each other’s thoughts in the same way?

Scholarly publishing has often been a technology early mover. Wiley published its first papers online in 1997, just beating the BBC onto the World Wide Web. Connections that existed only in the minds of the author and reader became realised through hypertext as paper linked to paper. With AI, scholarly publishing is playing catch-up, but our industry is world-changing. If we exploit the potential of AI to make connections, research will be the discipline where it can have the biggest impact.

This piece is part of our series, What does the future hold and how will we get there?

To read the full whitepaper, see below.