a-revolutionary-evolution-or-how-will-we-change

August 05, 2021

A little over year ago we argued that change in research and research publishing needed an ‘evolution, but faster’ model. What happened in the months since that post has certainly changed us all in many ways. And it has also shown us how much faster evolution in research is with us right now.

2020 made the already obvious super-clear: research plays a massive role in our world. The last year also brought home how rapid and open access to new and old knowledge (as much knowledge as possible)– from diverse researchers, disciplines, and geographies – is critical to make the impact we need.

What does 2020 show us about lasting change in research publishing? Let’s start by revisiting that panel of four researchers shared before the pandemic when we asked each to choose between revolution and evolution for research publishing. For the evolutionary biologist on our panel (who, of course, chose evolution) publishers did not add enough value by research dissemination, as arguably we did in the past. Our other panelists agreed. All told us that researchers use new, faster, more connected ways to share their work and to find what they want to read. They told us that researchers are no-longer dependent on publishers for dissemination.

Our panelists were also clear that peer reviewed journals must change what they do with research content. They recognized that peer reviewed research articles were only one kind of research output and that other options were available, like preprints and data. Even so, they told us peer reviewed research articles dominated as the way they chose to interpret and report their own research. Peer reviewed journals, they told us, need to re-focus on what matters more for research and for researchers, like how to enable transparency and openness. For me, the outcome of that demand for transparency and openness is research we can understand and trust.

For some context to those thoughts, every year more than 6 million postdocs and members of research faculties publish more than 2.5 million new articles in peer reviewed journal articles, adding to the more than 50 million already published and carefully maintained by research publishers. The system of journals and the infrastructure that surrounds them is what delivers these 2.5 million new articles into the published research record, is what means those articles are as reliable as they can be, findable and accessible, and ensures their availability for the long-term.

We presented our panelists with a binary choice: A tech revolution, “moving fast and breaking things”; Or a tech evolution, developing what we’ve got until research publishing is newly and better adapted to the world around us. The panelists swung towards developing what we’ve got, a tech evolution, and my answer is the same. Moving fast is great, but breaking things not so much. We should think different for something as important as the research record.

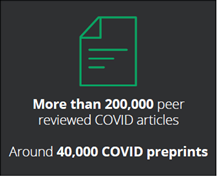

2020 showed us how true that is. For obvious reasons, peer reviewed research articles were published and preprints were posted in numbers far beyond what anyone was prepared for. More than 200,000 peer reviewed COVID articles in 2020, and around 40,000 COVID preprints, according to the Dimensions database. We’ve shown what we can do to change. We’ve all moved fast. We’ve renewed our commitment to what we do with and for researchers. At the same time we’ve highlighted systemic flaws and inequities, and learned more about what we need to address . We stepped up when it came to incidents where research articles perpetuated harmful stereotypes, when participant consent and research ethics were questioned, and to deal with concerns about possible papermills. This willingness to face and fix our mistakes is how Wiley delivers its commitments to quality and integrity. And it characterizes how we will get to a future like the one our panelists described, with more change but with what’s important intact, invested in, and nurtured. Our expectations are high, and our progress looks good:

- Preprints give us all an injection of what we most needed in any year, but particularly a year like the last: Speed. Preprints broke out of the science press into the media, and became mainstream in 2020. Understanding that preprints are early drafts without peer review became better-developed. Reservations were at least quietened by the urgency of addressing a pandemic-sized problem at speed and scale. The cooperative coexistence between preprinting and peer-reviewed journal articles we described a year ago became much more a reality. Journals are integrating with preprint servers, to enable authors who choose to share early versions of their work fast while it is being peer reviewed, then linking to the peer reviewed version of record in the journal. At its most extreme one journal, albeit not one published by Wiley, in 2021 will start to decline to consider work that hasn’t been preprinted. We’ve come a long way fast with preprints.

- Data-intensive science has for a decade been described as the ‘Fourth Paradigm’. It’s central in open science policy from research funders around the world. It’s been said repeatedly and by influential voices that soon all science will be data science. How do you marry that grand vision for a very real change in practice with the daily reality for many researchers, which is to report and interpret their findings after peer review in journal articles? In 2021 our answer is to continue to extend a requirement for researchers to add data availability statements to their research articles, to describe whether or not they shared their data. The choice about whether and where to share data remains with researchers, enabled by diverse data-specific repositories, and that’s great. Every day in December we published more than 180 new articles that did exactly that, and told readers something about whether and how they can access the author’s new research data. That number increases every day. We've still got a way to go beyond data availability statements to achieve that 'Fourth Paradigm' at scale, and data availability statements are a good first step.

- Last, if the most important changes are those that impact the most people (and I subscribe to that) then our fabulous progress in providing researchers with real choices for open access is just that: Open access is the most important of changes. Now we’re making more research more accessible to more people than ever before, evolving and transforming the journal system we have into a more open future. We’re so proud of the pace we’re setting in open access.

So where’s next? Our panelists asked us for change, for more openness and transparency. They, and stakeholders like them, are essential evolutionary pressure from one direction; frankly, finding our way through the pandemic has added more pressure, and reinforced the direction. In response Wiley combines the new and the old with strategic intent, investment, and care to get real hybrid vigor into research publishing. We’re moving fast and nurturing things instead of breaking them: Evolution, but faster.

To read the full whitepaper, see below.