how-old-wives-tales-helped-cure-scurvy

April 08, 2020

The history of scurvy is, by and large, relatively well-known. Associated with the high seas in a period of long-distance voyaging, scurvy had a significant impact on the health of crews from the sixteenth century onwards. On a long voyage, a ship could lose between a quarter and a third of its crew; in the 1740s, Lord Anson’s voyage around the world caused a significant outcry when roughly half of his 2000 men died from the disease.

We know now that scurvy is caused by a deficiency in Vitamin C. In the history of medicine, the popular story is that the cure for scurvy – a prescription of citrus juice – was discovered by the naval surgeon James Lind. Lind considered the principal cause of scurvy to be the diet of sailors, who often lived off biscuits and salted meats for several months. To find the best cure for the disease, Lind devised a series of experiments in which he tested different dietary supplements among his patients, including cider, vinegar, and seawater. Lind’s experiments showed that a measure of orange and lemon juice was the most effective and he published his findings in his Treatise of the Scurvy in 1753.

However, this was not the instantaneous moment of discovery that many imagine. Not only were Lind’s recommendations not implemented by the navy for another fifty years (with the efficacy of other remedies, such as sauerkraut, still being entertained), but Lind was also building on a long-running maritime tradition that had been stressing the effectiveness of citrus fruits for nearly two centuries. In the 1590s, the seafarer Richard Hawkins had already observed that ‘the most fruitful [remedies] for the sickness were sower lemons and oranges’ (Hakluyt Posthumus, 1622), and several years later in 1600, the East India Company commander, James Lancaster recorded the efficacy of three spoonsful of lemon juice each morning in preserving his crew from the disease. While the distribution of citrus juice within the East India Company was not necessarily consistent, it was not uncommon. John Woodall, Surgeon General for the company, noted that lemon juice was carried in ships in fair quantities, asserting it ‘a precious medicine and well tried’ (The Surgeons Mate, 1617).

So why is this important? The history of scurvy, like many other histories of science and medicine, problematizes the notion of discovery: that cures, theories, discoveries can be attributed to one person in one moment in time. Medical and scientific work is often the result of collaboration, and even awards such as the Nobel Prize have come under scrutiny for promoting the work of individuals over collaborative efforts. In his experimental trials, Lind was building on cultures of knowledge that went beyond the medical world, namely the customs of seafarers that had been established for centuries. My research, in general, focuses on the history of science and medicine in the maritime world, highlighting the knowledge, experience, and contributions of those, sometimes nameless, maritime workers, who do not otherwise feature in conventional histories of science or medicine. As the social history of medicine has highlighted in the last few decades, the history of medicine is inclusive of a wide cast of individuals and, then as now, knowledge creation was often the result of collaboration and the circulation of ideas within and across groups. When thinking about the history of scurvy, my interaction with the Royal College of Physicians archive has allowed me to extend this cast of characters in unexpected ways.

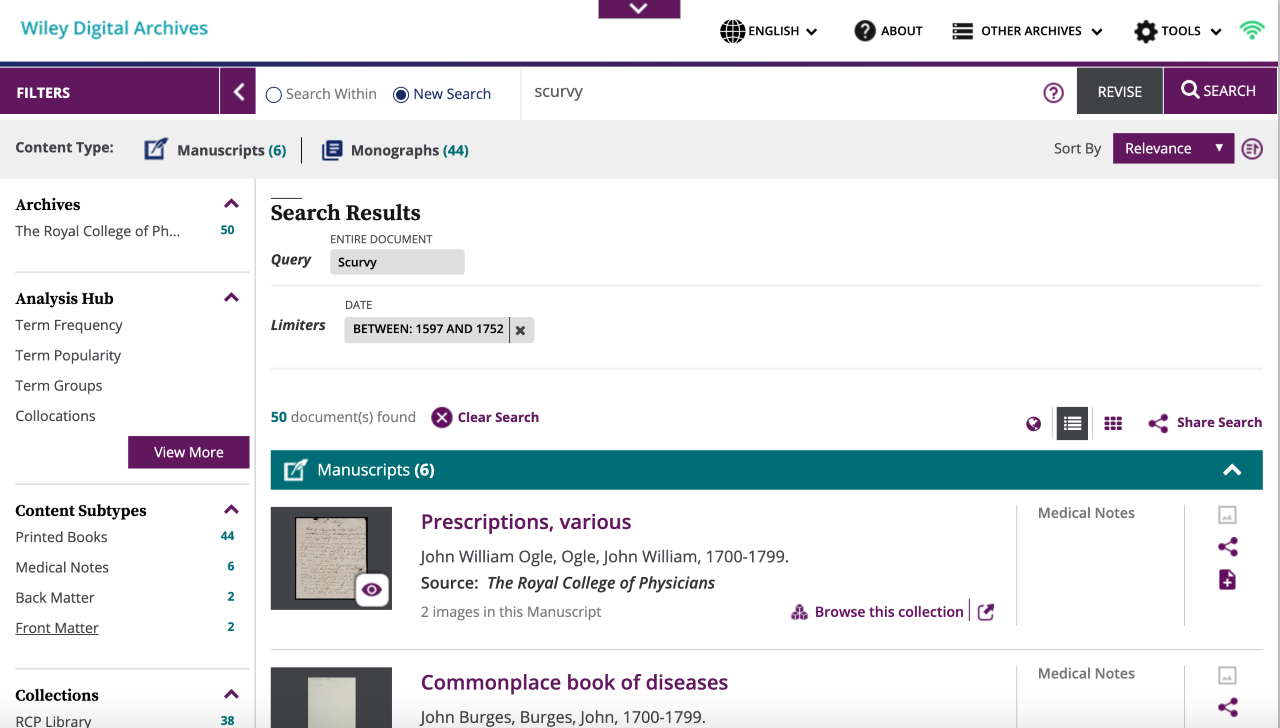

I approached the new Royal College of Physicians' digital archive in a rather predictable way: by simply typing “Scurvy” into the search function. I did limit this by date, from the earliest record to 1753 (the year of Lind’s publication), as I was interested in understanding the discourse on scurvy prior to the publication of his findings. The results were small but productive; the chief of these being a number of medical recipe books, which contained household remedies for scurvy.

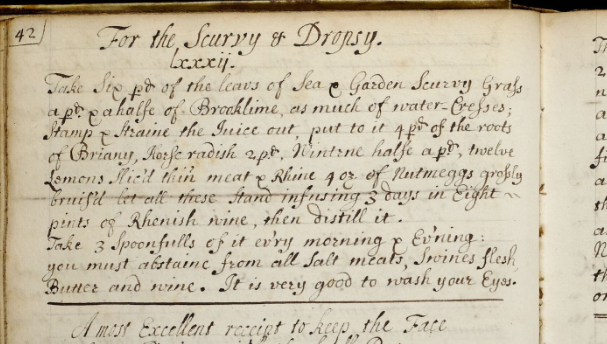

This turns us to an important point for, while scurvy is a disease often associated with the sea, it was also experienced on land. It should have been of little surprise to see the inclusion of cures for scurvy in these books, and yet I had not previously considered them as potential sources. Remedies varied, and in the handful of recipes I encountered, I was surprised to find that nearly all included citrus fruits. One recipe book by Lady Sedley (1686) has a recipe for curing ‘Scurvy & Dropsy’ on page 42, which includes, among other things, ‘twelve lemons sliced thin’ infused in wine with a variant of spices.

Another collection of medical recipes and prescriptions from 1690 described alternate remedies for those with cold or hot constitutions that both contained lemon juice. The recipe book of 'Madame Pyne' (1644-1691) also contains a recipe for a drink against the scurvy that includes “the rinds of four oranges” in addition to other ingredients such as juniper berries and ale. Given the inclusion of citrus fruits in these recipes – appearing in this small sample as a common denominator – we find some recognition of the value of citrus fruits in fighting scurvy in domestic settings long before Lind’s famous experiments.

These sources have led me to consider alternative ways to broaden the history of scurvy. I was previously interested in going beyond medical professionals and highlighting the knowledge and practices of seafarers and other lesser-known sea-surgeons, but here we see the engagement of women – albeit elite women – in seeking to confront the disease. Recipe books have become a notable focus of much scholarship on the social history of early modern medicine in the last decade or so. This has been aided by the digitization of a great volume of recipe books by the Wellcome Library, which I shall draw on going forward to furnish my sense of scurvy in these alternative contexts. I am particularly interested in documenting the circulation of knowledge between sailors, women, and doctors, for in the few recipes I have encountered we do see a number of women adapting the recipes of physicians. To what extent did these remedies intersect with the common knowledge of sailors? These sources, on the Royal College of Physicians and Wellcome digital archives, bring the history of scurvy from the ship to the shore, and in particular into domestic settings, allowing us to connect land and sea in a more integrated history of scurvy.

To learn more about the history of science and medicine, or to request a free trial, visit the Royal College of Physicians archives page on Wiley Digital Archives.