science-and-journalism-in-the-age-of-fake-news

October 26, 2018

If we believed everything that was reported about the research published in our journals, we’d be riding our cloned wooly mammoths to work, eating chocolate to lose weight, and drinking red wine to cure cancer.

This joke opened a recent discussion at The New York Academy of Sciences, moderated by Wiley’s Chief Product Officer, Jay Flynn. The panel, featuring Nsikan Akpan from PBS NewsHour, Amanda Aronczyk of WNYC, David Freeman of NBCNews.com, and Amy Marcus from The Wall Street Journal, was there to debate the role of science and journalism in the age of “fake news.” After each statement, the audience raised their two-sided paddles—red for disagree, green for agree—and after each debate they raised them again. How many minds would the Academy change that night?

Fake News and Social Media

Social media was first up, as the panel debated whether or not our use of social media is driving the public’s misunderstanding of science. According to the Pew Research Center, 68% of Americans get their news from social media, and 56% don’t trust the news they get. Some on the panel felt that social media was self-regulating: there’s so much information on social media that there’s a self-correcting mechanism for accuracy. And while science and health aren’t among the most popular tweeted topics, hot button issues like vaccines and climate change tend to drive people apart. As the panel described, we want to be part of a tribe and prove ourselves to that tribe by sharing stories that show off our ideological beliefs. Maybe the challenge is that social media is intended for us to spark conversation, not receive news. We should use it to enlarge the world and our access to people and ideas.

Science and Credibility

Next the panel tackled the statement: To counter science denialism, it is a scientist's responsibility to communicate the implications of their findings as widely as possible.

The tension in this statement came from the fact that while it might be scientists’ responsibility, it might not be within their skill set. Discovering true things about the world is hard enough as it is, so whose job is it to communicate this in a way that the public can comprehend?

Maybe it’s the institution, maybe it’s the journalist. Regardless, the panel encouraged everyone to talk to journalists. If you receive public funding, then think of the public as an employer.

One thing everyone agreed on was the fact that science is a communal enterprise. Whether you practice it daily in a lab or in the field, or benefit from it, science belongs to us all. As Amy Marcus described, “science is like art, it doesn’t just belong to one group of professionals. It’s something that we all should engage in and be drawn [to]. It’s about marvel and wonder and asking questions that touch all of us.”

What should we believe?

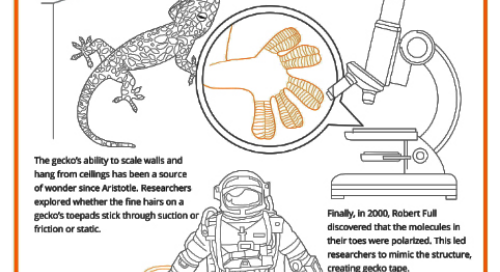

We then talked about how all the conflicting stories on food safety drive everyone crazy. Are carbs good? Is gluten bad?

Context is king for this discussion. If only, at the beginning of every article, there was a disclaimer that science is evolving, that each study builds on what comes before. If the public understood this, it would go a long way. Journalists try to emphasize the weight of evidence. A single study is nothing without the larger context, but it’s a challenge when they’re pressured to write short stories with soundbites or catchy headlines.

The panel also turned the tables back on scientists: we report what you write, so even when we try to place it in context, scientists are still the ones publishing papers that go back and forth.

At the end of the day, journalists make value judgements about what to cover and that is most easily done when they can work not just with a published paper, but with scientists themselves.

Grabbing the public’s attention

Finally, the conversation turned to headlines. Are those sensationalized, eye-catching headlines inherently in conflict with the rules of good science journalism?

The journalists argued that headlines are a necessary part of the game: they are a wakeup call. They get people in the door to read the article, which is ideally full of nuance, context, and a compelling take on the research landscape.

Science news isn’t just competing against other science or health stories; it’s competing against Kim Kardashian and Megan Markle.Headlines need to be gripping. The panel also pointed out that science headlines aren’t for scientists.

The panel also argued that scientific article titles could learn a thing or two from headlines. Academic paper titles are so dense and jargon filled that it can be a real challenge to figure out what the paper is talking about. We need article titles that demonstrate what’s compelling about the paper, why it’s important, why these scientists devoted time and energy to studying it.

“Explain it to me as if I’m a science-minded 15-year-old,” Nsikan Akpan said. “I might not understand it, but I’m interested.”

With this panel, The New York Academy of Sciences taught me several things. First, it reinforced just how hard it is to change someone’s mind. Though some opinions shifted throughout the evening, what emerged instead was a nuanced look at the balance of science news: juggling clicks with context and nuance with word count. And while the challenges of trust and reliability remain, one thing is certain: science belongs to everyone, and sharing it as widely as possible is a critical part of moving our society forward.